History & Information

The history of the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office began prior to California receiving statehood. In fact, when California became a territory of the United States after the Mexican-American War in 1847, the state was under control of military law. The vast countryside that started north of San Francisco Bay and stretched to the Oregon line and west of the Sacramento River was declared the Sonoma District. The District Agent was a gentleman by the name of Mariano Vallejo and the acting Sheriff was one, Thomas M. Page.

The headquarters for the Sonoma District were located in the small village of Sonoma and remained there until all county offices and government were moved to Santa Rosa between the years 1845 and 1855.

After California gained statehood, the area of jurisdiction was eventually reduced to what constitutes present day Sonoma County, in addition to the southern part of Mendocino County from Ukiah and Big River south. It wasn’t until March of 1859 that the boundaries of Sonoma County were changed to what we have today.

During these early years, Israel Brockman served as Sheriff. Appointed in 1849, Brockman would eventually be elected to his post and would serve as Sheriff until 1854. Benjamin Snoddy and James Reynolds served under Brockman’s command and in 1852 they became the first sworn deputy sheriff’s of record.

The first jail in Sonoma County was located on General Vallejo’s property in Sonoma. It remained operational from 1850-1853. The building was constructed of adobe so jailbreaks were common, despite the fact that inmates were often times kept in chains. Inmates used various methods of escape, including lock picking, filing bars, tunneling and some prisoners simply walked away. One night, in 1852, the notorious Sarabouse d’Audeville escaped after cutting off his leg irons. The soon to be executed d’Audeville left two men sleeping and a letter of farewell on the table. He was the third prisoner under a death sentence to escape from this jail.

In her book, Santa Rosa – A Nineteenth Century [Photo courtesy of Depot Park Museum] Town, historian Gaye LeBaron relates one of the first documented hangings to occur in Sonoma County. It occurred in the spring of 1854 when a mule rustler by the name of Ritchie was accused of absconding with a band of mules. Some of the animals belonged to Captain Hereford, who lived on Santa Rosa Creek, and two were the property of another valley settler, Mart Tarwater.

Ritchie was tracked down, arrested and brought back to the old Carrillo adobe. Several Santa Rosa settlers opposed his immediate hanging, which was considered the customary punishment for the times. James Bennett, the Bennett Valley pioneer and soon-to-be legislator, was rumored to be among the men appointed to escort Ritchie to Sonoma City, which was still the county seat. The next day, Ritchie’s body was found hanging from an oak tree on Joe Hooker’s property in Agua Caliente. The grand jury convened, but all participants who showed up for the inquest, wore sprigs of oak in their buttonholes and refused to testify.

A new bill was passed which authorized a vote concerning the removal of the county seat. As a result of the passing of this bill, an election was held in Sonoma County. On September 6, 1854, election poll results showed 716 to 563 votes favored moving the county seat from Sonoma to Santa Rosa. Santa Rosans staged a victory celebration that lasted for two full days.

The County’s third courthouse at Sonoma (or the building briefly utilized as such), was scarcely mentioned in record and apparently has no relic. December 13, 1854, marks the first documented plans of an official courthouse and jail. When the county seat was moved to Santa Rosa, a jail and courthouse were built on the northwest corner of Mendocino Avenue and 4th Street. During the summer and fall of 1855, the courthouse/jail was built for $22,107.23, and included a lower story with space for the sheriff’s office, jail and judge’s chambers.

In 1856, A.C. Bledsoe was elected Sheriff. He only had six deputies, three of which were jailers. During this time, deputies were sworn in only as needed and served specific jobs, such as law enforcement, tax collecting, jailer, prisoner transport to San Quentin, and janitorial services. Other deputies would serve an entire year then have to be sworn in again to serve for another year at the Sheriff’s pleasure. Deputy Jacob M. Gallagher, was the first permanent jailer and held this position from 1856 to 1861. A contemporary of Gallagher, Deputy Nalley, was sworn as the first recorded bailiff.

The first few decades were a period of growth and stabilization of Sonoma County’s government. In the mid-1850’s, problems included lynchings and later a Squatters’ War at Bodega Ranch that involved mercenaries from San Francisco. Luckily, no hostilities erupted, there were no shots fired, negotiations were conducted and the mercenaries went home.

At the beginning of the Civil War a large segment of the population in the county was sympathetic with the South. This caused a lot of political tension in the county. As a result of this tension, Sheriff Bowles had 23 sworn deputies in the early 1860’s. During another Squatters’ War in the Healdsburg area, a standoff occurred between Sheriff Bowles, his 200- man posse and 60-armed squatters. One of the posse was shot and killed by a squatter and the squatter was not held for the death. This same thing happened to a deputy at Stony Point while executing a court order, but the shooter again was not held to answer for the incident. These were the first two men to die while acting on behalf of the Sheriff’s Office.

In the mid 1860’s there was a hanging for a murder, which was the only execution in Sonoma County. The murder was documented with the following historical quote:

“On February 7, 1865, Mrs. Ryan was brutally murdered by her husband Michael Ryan, by striking her on the head with a pick. They had been residents of Santa Rosa but a short time and lived unhappily together, the husband being addicted to dissipated habits. On June 29th, he was arraigned before Judge Sawyer and sentenced to death, this being the second conviction of murder in the first degree, which had taken place in the county since its organization. The murderer was decreed to pay the extreme penalty of the law on the 17th of August, but in the meantime a stay of proceedings was granted upon motion of a new trial. He was hanged on March 23, 1866, within the jail yard of Santa Rosa – the only execution which, up to the present time, 1879, has occurred in Sonoma County.”

With the maturing of the sciences, law enforcement adopted new tools; the telegraph was used extensively and the implementation of “mug shots” came about in the late 1860’s. Like today, deputies investigated robberies, burglaries, assaults and homicides. The difference between today’s offenders and yesterday’s was that a great majority of the culprits were tramps – tramps in every sense of the word: non-resident, homeless, down-and-outs, transients. The only similarities were the homicides. A great majority of the parties involved were county residents whom knew each other.

In February 1871, Sonoma County had its own stagecoach gang of robbers, which worked along the mail road from Healdsburg to Ukiah. They were known as the Houx Gang and consisted of John Houx, “Big Foot” Andrews, Lodi Brown and “Rattle Jack.” Rattle Jack and a stagecoach passenger were killed during their fourth hold-up, and several other passengers were wounded. With a concerted effort by Sheriff Potter and Wells Fargo, a Wells Fargo agent went under cover. After the sixth robbery, the law went to work arresting the gang that by then had grown to five members. They were apprehended in various locations in the north county. Even though armed, not a shot was fired by either side. John Houx spent about a year in prison then was paroled; “Big Foot” was killed in prison; Lodi Brown was paroled and left the state. The remaining two were released – not guilty.

As stated previously, deputies were sworn in for one year or less and re-sworn for a new year. With such hiring practices it would be difficult to be a career lawman. However, one deputy, Edward Latapie, was able to work up the ranks and was elected Sheriff. He had first been sworn in as a deputy in 1859 and was elected to office in 1872. He retired in 1876.

In 1876, the third lynching occurred. However, this event was different than the previous two. Charles Henley, 57-years-old, would let his hogs run wild up around Bidwell Creek, much to the irritation of one of his neighbors, especially his neighbor, James Rowland. It finally happened one too many times and Rowland kept Henley’s hogs. Henley went looking for them (accompanied by his shotgun) and finally found the wayward swine on Rowlands property. An argument ensued between Rowland and Henley, which came to a sudden end with a shotgun blast killing Rowland. That night Henley rode into Windsor and surrendered himself to a deputy sheriff. Henley was held for a month at the county jail.

Word spread about the death and on the night of June 9, 1876, nightriders went to the home of Jailer Wilson on Fifth Street. Terrorizing Wilson’s family, they took Wilson down to the jail and forced him to open Henley’s cell. As four masked men grabbed him, Henley cried out: “Oh Lord boys, spare my life.” They were the last words he said. Quickly gagged, he was trussed up and taken to Gravel Slough (west Roseland District) and lynched from a tree along the bank. A reward went out by Sheriff Wright for $500 for the capture of the perpetrators. It was later increased by $500 from the Board of Supervisors and again by $1,000 from the California Governor. No one was ever arrested and Henley’s widow eventually claimed her husband’s body. This was the first time a suspect was taken from a Sonoma County police agency by force and it would happen again.

In the mid-1860’s, the county jail was designed to hold approximately ten inmates, with a maximum of thirteen. In the late 1870’s, there were 22 prisoners, which required an extra jailer. Everything had reached its maximum in the jail. For over seven years, the Grand Jury and the Sheriff requested and pleaded with the Board of Supervisors for a new jail, and if not a new jail, than at least an extensive renovation. The Grand Jury responded with the following statement in 1877: “The jail is clean as possible under the circumstances, but the stench from the [privy] is so great as to render it unfit for the confinement of human beings.”

A glimpse of the treatment of inmates shows that they were given two meals a day (8 a.m. and 3 p.m.) at a cost of 35 cents per day. The guard was paid $1.50 per day; this was not the jailer. The purpose of the guard was due to the in-house count. It had reached 22. The Grand Jury of 1878 wrote: “The jail is neat and clean but very unsafe.” And in 1879: “Not a safe place to confine prisoners.” Every Grand Jury up until the year 1882, said basically the same thing.

Finally, the Board of Supervisors decided that all county departments were to be in one building, and agreed to have a new combination Courthouse and county offices built. As a result, the seat of county government was moved across Fourth Street to the plaza in the center of town and it was finished in 1885. The Sheriff’s office and jail were in the basement. The office had three rooms, one 21 x 35 feet, the second 14 x 27, and a storeroom 19 x 21 feet. The height of the walls was 12 feet (the shortest in the building). The jail section was 38 x 59 feet with twelve iron cells 7 x 7 feet, and three cells 5 x 7 feet. The entire jail was lined with iron plates. With the establishment of a new office and jail the Supervisors officially wrote a new menu for inmates:

“Jail meals for prisoners –

Breakfast: ½ loaf of bread; ½ lb. steak, potato, coffee.

Dinner: ½ loaf of bread, ½ lb. mutton stew, beans or stewed fruit, potatoes, tea.”

The jail was adequate for only four to five years. Because the law required separation of classes of prisoners, there was such a lack of space that the County was forced to build another jail at a cost of $40,000. The construction lot, 60 x 140 feet, was on 3rd Street just east of Hinton Avenue in Santa Rosa. It was built in 1891-1892 with two tiers of cells and one cell was designated specifically for women. It didn’t take long before the residents of this hoosegow lettered on the walls “God bless our Home” and “Eat, drink, and be merry.” The jail was noted as one of the best and most substantial on the Pacific Coast,” until May of 1892, when a convicted murderer escaped. The statistics at the end of 1892, the first full year of the jail, showed that there were 500 prisoners of which 346 were misdemeanants. At the time, there were thirteen homicides and attempted homicides, at a rate of one per 2,960 people.

One of those convicted of murder was George Bruggy. He escaped by sawing through the bars of the jail and was captured a few weeks later. After numerous reprieves on his death sentence George Bruggy escaped once again, this time, never to be recaptured.

In 1893, Sonoma County was shaken by the largest earthquake in recorded history, up to that time. There was some damage to county structures, but none to the new Sheriff’s office/jail. There were no physical injuries to the inmates. When repairs were made to fix minor damage in the jail, electricity was installed in the Sheriff’s office and by 1904 the office had a telephone installed.

Early in 1897, Sheriff Samuel Irwin Allen owned a couple of young bloodhounds called “Sam” and “I” (Eye), to be used as trackers. These whelps were the pioneers of our K-9 units. Deputy Ed Wilkinson began our modern day Deputy Dogs in the late 1960’s with his Doberman pincer “Cupid.”

The quake of 1893 was a practice exercise for the North Bay, the Sheriff’s Office and the jail. On April 18th the famous 1906 earthquake occurred. While all the brick buildings in Santa Rosa collapsed, including some wooden structures, the county jail of 1892 withstood the shake. The town counted over 100 killed, but no major injuries were reported among the prisoners. The jail remained in use until it was torn down circa 1969, some 76 years later.

The county was focused for the next couple of years regrouping its losses and rebuilding. With the courthouse totally disabled, a temporary structure was built across Hinton Street next to the Hall of Records. The Sheriff’s Office suffered only minor damage. When the new courthouse was dedicated in 1911, the hall of Records was included in the building. The Sheriff’s Office took over the Hall’s old site off Hinton and Third [Reward Poster] Street adjoining the combination Office/Jail on Third Street. A new building was erected and the jail was expanded into the front of the old Sheriff’s Office resulting in a reverse “L” shaped structure when

viewed from Third Street.

Crime and law enforcement continued its dance, each switching the lead to sounds of guns and wails of victims. In July 1910, the county and Northern California was shocked to learn about a triple murder above Cazadero at Lions Head ranch. Twenty seven-year-old “Harry” Yamaguchi, a ranch hand who worked for Enoch Kendall, committed the killings. On the July 23rd, he killed Enoch, his wife and their son. The bodies were dismembered and parts were found in the home stove and cast about the property. The Governor of California offered a reward of $500 and the San Francisco Examiner added another $500. Yamaguchi fled to the East Bay and revealed the murders to an acquaintance. After being notified by the acquaintance the police arrived, but Yamaguchi had gone and was never found.

Apparently, since the County was spending vast amounts of tax dollars because of the quake, a decision was made to have every office display the new courthouse on its letterhead. To assist the county spending, the Sheriff was authorized, for the first time, to hire permanent deputies. Four deputies were sworn in by Sheriff J. K. Smith, at a wage of $1,025 per year. Sheriff Smith’s salary was $2,000 per year.

On December 2, 1920 in San Francisco, three members of the Howard Street Gang lured two young girls to a home, where they were “brutally assaulted.” The three members, Terry Fitts, George Boyd and Charles Valento, promptly left the city, but their trail was traced by two San Francisco Detectives to Santa Rosa. The detectives contacted Sheriff Petray and they combed west Santa Rosa in search for the perpetrators. They were found at 28 West 7th Street and in a gun battle, Sheriff Petray and Detectives Jackson and Dorman were killed. In her in-depth history of Santa Rosa, Gaye LeBaron writes that in December of 1920 a mob of people disguised and masked, “overpowered” jail personnel and removed the three prisoners who were being held for the murder of Sheriff James Petray and two San Francisco police detectives. The mob took the three prisoners to the Rural Cemetery on Franklin Avenue. An area 50 feet from the street was lit up by car headlights. The three bound prisoners were dragged beneath a locust tree and lynched. The leader of the vigilantes made everyone remain at the grisly scene until the three were dead. It was the next to last lynching in California.

During Prohibition, the main task of law enforcement was to suppress the making, shipping, dispersing and consuming of alcohol. The raiding of county residences or barns for the illegal product was almost a daily occurrence. From Sonoma to the sea, bottles and barrels were confiscated and the suspected parties arrested. A location four miles west of Santa Rosa had five stills producing 680 gallons a day “of the best moonshine obtainable in the county.” Guilty suspects were generally sentenced to four to six months in jail, plus a fine.

The jail count for arrested persons in 1927 was 745. Liquor violations accounted for 104, while disturbing the peace was 115. The infractions occurred mostly at the summer resorts and dance halls. Most violations were handled by the justice courts in the outlying communities of the county without them being brought to the county jail. Many communities had their own places of incarceration; wooden boxes called a jail and paid for by the respective townships through taxes.

In 1928, Guerneville got a new jail. As reported in a newspaper article in February 1928: “Guerneville is to have a branch ‘office’ of the county jail for the accommodation and incarceration of drunks, peace disturbers and other miscreants during the summer, when the population of the Russian river section is larger than that of the county’s three chief cities combined."

Through the efforts of Supervisor Willard Cole at the suggestion of Sheriff Douglas Bills, the count has acquired a huge steel tank from the phenol plant at Guerneville, now being dismantled. As large as a boxcar, which is its general shape, and of solid steel, the tank will be remodeled, equipped with sanitary conveniences and barred doors and windows, and divided into two or three cells. It will stand on a strip of land just outside the town, between Rio Nido county road and the railroad right of way.

This plant will be of great convenience to county officers and special deputies in the river section. Under present conditions, sheriff’s officers from Santa Rosa are called upon at all hours of the night during the resort season to go to Guerneville and bring arrested persons here, and later have to return them to the river town for hearing. Otherwise the special deputies bring them to the jail here, in which case it is necessary to bring them back to [Text Box:] Guerneville for trial.

Keeping the prisoners in a convenient local ‘county jail ‘ will pay for the cost of the tank in a short time it is estimated.

Guerneville at one time had a prison, a wooden structure, for the temporary incarceration of arrested persons. But the first man, who decided he did not want to remain locked up just kicked the side out of his cell and walked out, so the jail was abandoned. Monte Rio has a strong and, sufficient branch county jail at present.

At the height of the resort season, because of the great influx of a temporary population, many arrests were made in the river section. They are mostly for misdemeanor offenses, peace disturbance at dances being the most common offense.”

Thus, the first of three future and “permanent” satellite county jails came into being. Prior to this time, jails were of local jurisdiction, in city police departments and judicial townships. The future would see the construction of the Honor Farm/North County Detention Facility and the Sonoma Valley Substation. The holding cells at Guerneville and Sonoma are no longer used.

The “dry” Roaring 20’s gave way to an even more “dry” and “depressing” 1930’s. Besides, or because of, a lack of jobs the labor unions were very active, not only in industry but also in agriculture. Many people at this time put union recruits in the same category as communists. The political atmosphere was tense as well as dangerous in 1935.

In 1935, a 77-year-old rancher, Al Chamberlain, was a person trapped in the past. He had acres, horses, cattle, and was a rancher in every sense of the word. He lived in the hills around St. Helena Road and couldn’t (or wouldn’t) master the mechanical things of the day, especially automobiles. Even in the 1930’s, he rode to town on horseback and was teased and became the butt of jokes. The city had problems with him because of the smelly corral he had near the center of town. The city ordered him to close it down with Chief O’Neal signing and delivering the order. Chamberlain’s problems with cars came to a head when he struck a pedestrian. O’Neal charged him with reckless driving and he was sentenced to a month in jail and $100 fine.

It was June 1935. Life and society had become too much for Chamberlain to deal with. He loaded up his guns and came to Santa Rosa. He walked into the police station and saw Chief of Police O’Neal. He shot the Chief three times and left, heading across the parking lot to the Sheriff’s Office intending to shoot Sheriff Patteson. Patteson heard the shots and went out unarmed. He saw the man with two guns. As they walked toward each other Chamberlain asked him “Are you Harry Patteson?” The Sheriff said no as they continued towards each other. Then Chamberlain recognized him, raised his gun and fired a shot, missing. Patteson hit Chamberlain with a body block and they both went down. Patteson, with the aid of two citizens, captured the old man. Chief O’Neal died two days later and Chamberlain later died in prison.

Two months later, Sheriff Patteson had his hands full with union organizers. There were marches by the organizations in the county and there were strikes by more than 500 crop pickers. Sheriff Patteson deputized in excess of 140 men. Later his posse grew to 500 special deputies. He was ready if there was a riot out in the fields or packing plants. Additionally, during this turbulent time there were more than 200 vigilantes looking for “Reds.” Night riding vigilantes rounded up some registered communists and took them to a warehouse down at the railroad tracks in Santa Rosa. There they made the captives kneel and kiss the flag. A couple refused and were promptly beaten, tarred and feathered then thrown into a car.

A parade of cars went around and around the downtown Courthouse, past the Santa Rosa Police Department and the Sheriff’s Office, firing guns, honking and yelling. No deputy or police officer made an appearance at the sound of the disturbances that night. The two beaten men were taken out to the City limits by the nightriders and given 24 hours to get out of the County with their families.

Twenty-two people were charged with various crimes against the two men and the State. At the preliminary examination among the defendants were two highway patrolmen, a member of the coroner’s office, a future deputy sheriff and a future police officer. After the examination, ten defendants of the 22 charged were discharged. The remainder were found not guilty at trial.

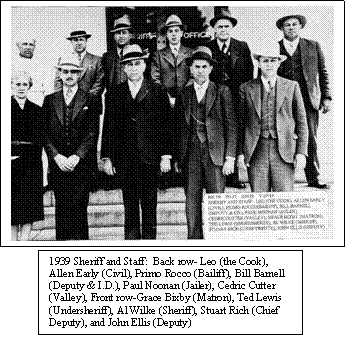

Patteson’s career was interrupted by the election of Andrew Wilke in 1939. Wilke’s staff consisted of ten deputies. Among these were future sheriff’s captain Bill Barnett, Bill’s future boss, Sheriff John Ellis, and matron Grace Bixby, grandmother of television star Bill Bixby. By this year the Sheriff’s Office had a radio and dispatcher.

Wilke’s term was during the beginning of World War II. Being close to the Bay Area, and with two air bases in the county, the military men had to go somewhere to let loose. Many would visit the River Area on Liberty. Big Bands, bars, and ladies of the night all prospered. Almost all visitors that came to the river resorts came from places where law enforcement officers wore uniforms. The Sheriff’s Office had no requirement to wear a uniform, but those who worked and lived in the river [Text Box:] resort area had to have them. When a plain-clothes deputy would put the arm on some miscreant, a confrontation usually occurred. To make their job easier, Resident Deputies Tunis “Pete” Bever, “Tex“ Nicholes and Bill Moore purchased their own outfits, which were basically tan, with some personal variation. The shirts they bought to wear didn’t match. They were issued badges by the Sheriff's Office, and as there was no Sheriff’s insignia in existence, their sleeves were slick.

Sheriff Patteson was re-elected in 1943 and stayed in office for another 15 years, with a total of 19 years as Sheriff. His record tenure still stands today.

Post war law enforcement continued in the pre-war style, responding to calls, on-view violations, and helping overcome family tragedies. Such a tragedy happened in November 1949 at Wohler Ranch. The screams of five5-year-old Esther Silvas and the repeating sound of a shotgun attracted a neighbor rancher who armed himself and ran to the scene. At a farm worker’s cabin on the Wohler property he found three bodies, Clyde Howard 23, his wife of one week Louise, and Esther Silvas’ mother, Maria. A few minutes later Tony Abaya was shot at his cabin at the Grace Ranch. Other armed neighbors came to the scenes and promptly called the Sheriff’s Office. The suspect, Polcerpacio “Henry” Pio was captured on the outskirts of Santa Rosa by the police at College Avenue and Link Lane. Pio gave no resistance. His loaded shotgun was in the car. Sheriff’s Investigator Robert Dollar, with others, found fifteen gun shells at the first cabin and nine at the second. Pio admitted to shooting the four. He was sentenced to life with the possibility of parole.

The post war era, 1945 to 1960, was a boom time for the County and the population grew with both residents and vacationers. Law enforcement was always doing catch-up with both the criminal element and casual violators. During the summers, the Sheriff would hire “summer” deputies to work in the River Area and Sonoma Valley. Many were schoolteachers on summer breaks, while others were college students breaking into law enforcement.

The Valley Substation would get three or four temporaries and the River Substation would have as many as six or seven. Even though there was radio dispatch for the deputies the broadcast signal didn’t reach into the outlying areas of the county. They were too far away or intervening mountains and hills blocked the signal. To get a deputy to respond to a call out in the hinterlands the dispatcher in Santa Rosa would land wire the sub-station. A red light would turn on outside the station so when a deputy saw the light he would call Santa Rosa for his instructions. In the central county there was no problem except when one patrolling deputy wished to talk to another. If one deputy wanted to, he had to request the dispatcher to connect him to a direct two-way communication. The dispatcher threw a switch so the two deputies could talk to each other with dispatch listening in. After every transmission by dispatch, F.C.C. dictum required them to state the Sheriff’s station call letters, “KMA 392.”

The dispatcher’s office in the main office was at the front door of the building alongside the main hallway. The Sheriff’s secretary, besides regular duties, handled the front counter during the day while the dispatcher handled the swing and graveyard shifts. Though these two shifts were the busy hours for deputies, the number of inquiring people assisted by the dispatcher was low because these were not regular business hours. There were four dispatchers to cover all shifts. The dispatch office was a single room 10 by 10 feet. There was a little room to the side, with sound proofing, where the teletypes were located. Other dispatcher duties, besides logging phone and radio calls, included monitoring the teletype and occasionally “baby-sitting” a newly arrested person when the jail was to busy booking a large number of incoming arrestees.

Patrol cars during the early 1950’s were, by today’s standards, very basic. There was a white spotlight on the driver’s side and if the deputy had to go Code two or three, he slipped a red lens with springs over the light. The siren was driven by an electric motor. When engaged, the electricity drawn from the car would slow the car down. The vehicles were unmarked and were mostly two-door sedans. They were without a divider between the front and back seats as there are today for deputy protection. In some cases an early 50’s car had a 6-cylinder flat head engine, an example of law enforcement playing catch-up.

The County would experience mob violence in the second half of the 20th century. The first occurred in March 1953, at Los Guilucos School for Girls. This was the official title of the California Youth Authority for the juvenile female detention facility. (This would eventually become the County’s Juvenile Hall and the States Police Academy).

The inmate count at Los Guilucos was over 150. Led by a young teenager, a group of twenty escaped, breaking furniture, windows and anything valuable. After a night of chaos, destruction and freedom, some 30 girls were injured. The Sheriff’s Office, Santa Rosa Police, California Highway Patrol and Sonoma State Hospital Security force from Glen Ellen quelled the riot.

Election year 1958 saw John Ellis, Chief of Police in Sebastopol and former deputy, run for Sheriff on the platform of having patrol cars marked and deputies in uniform. Very few police agencies in the state were without public identification. The platform proved to be a winner, however, it would be a year and a half before the promise appeared on the streets. What type of uniform, its material, shoulder patch design, and patrol car markings took time to select.

In the mid-1960’s, the new uniform to be worn consisted of forest green “Ike” jacket and pants with blue and yellow stripes around the cuffs of the jacket and down the legs of the pants. Shoulder patches were silver lettering on a blue field and Vallejo's Petaluma Adobe in the middle. The hat was Ellis’ favorite: a Stetson 3X Beaver, Open Road, light gray in color. The necktie was blue, similar to Greyhound Drivers or the Boy Scouts.

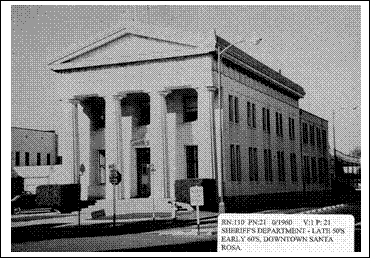

Under John Ellis’ administration, some modern, contemporary ideas and facilities were implemented. The County had purchased a 470-acre parcel north of Santa Rosa in 1955. With the opening of the freeway in 1955 and suburban development of east Santa Rosa, the County was looking at more expansion of its legal offices. In 1962 plans were drawn up for the construction of a new courthouse combining the Probation Department, Courts, County Clerk’s Office, Sheriff’s Office and Jail. The Jail of 1892 with the Sheriff’s Office and the Courthouse of 1910 were long outdated.

The first women deputies in uniform did not work full time, but on a time-share basis. They were Viola Maguire, Loretta “Mom” Derry, Esther Joliff and Dorothy Jarvis. They worked the jail, patrol and the courts.

It was also at this time that the racial line was crossed and then eliminated. The first African American hired by the Sheriff’s Office, and probably the first in law enforcement in the county was Jim Brown. He was hired around 1962-63. College educated, he was at first a jailer then made sergeant. He eventually made lieutenant and was night watch commander. Lt. Brown retired in January 1985.

Prisoners in civilian clothes would no longer be marched across Hinton Avenue from jail to court every morning in a chain gang. It was a daily ritual for friends and many other people to line up on the sidewalks and watch the procession proceed to Court. In 1965, the new Hall of Justice and Jail was completed at a cost of $3,854,000. The new jail had a capacity of 214 males and 36 females and was occupied in January 1966. There were a total of 75 sworn personnel, including all sheriff’s administration, secretaries, clerks, radio dispatchers, jailers and deputies.

The new Sheriff’s Office was expansive. The front lobby waiting area was 15 by 15 feet and everybody in the patrol division from detective on up had an office. The jail had a sally port for patrol cars to drive in with in-custodies, which eliminated not having to walk them from the car across a parking lot to the jail.

The jail was very modern with electric sliding doors controlled at a main panel. An intercommunications system allowed jailer/deputies to keep better security over inmates as well as themselves. The intercom even extended to the three court holding cells on the second floor in the Hall of Justice. Bailiffs could notify the jail when prisoners were ready to be picked up or ask for delivery of one. The intercoms fell into disuse with the advent of personal radios issued to the bailiffs. Prisoners for the first time were brought from jail to the courts contained in a totally enclosed cement walkway across the top of the building. This pretty much eliminated the chance of an escape.

It would be two to three years before all detainees would be in jail clothing when appearing in court. Until a person was sentenced they would appear in their personal civilian garb. It was commonplace to have three or more prisoners sitting in court in plain clothes with only one deputy/bailiff as guard. He would not have a weapon, radio or regular street equipment with the exception of handcuffs. Since there were no phones in the courts, many times it was necessary to leave the court unguarded while in session. Surprisingly, attempts to escape were next to nil.

In 1970, Don Striepeke was elected Sheriff. The change in leadership was a change from old style enforcement to modern law enforcement. More extensive communication facilities, more extensive training, tactical scenarios with special squads, special enforcement units and many others were implemented. Sheriff Ellis opened the door for the new Sheriff (Don Striepeke) to be ushered it in.

During the late 60’s and early 70’s, there was social unrest in Sonoma County. The Hippie culture was underway with its related drug use, the Viet Nam War and its anti-war demonstrations, the county was a busy place to work.

A pivotal year for the jail was 1972. No longer would deputies be assigned as jailers. The first correctional officers came from state academies trained specifically in how to handle prisoners while in custody.

The biggest event for the office in 1972 was a jail riot. On March 7, 1972, a riot broke out in the County jail. The disturbance started around 5:30 p.m. when an unidentified inmate violently tossed his food tray onto the floor. Within minutes, 145 inmates were rampaging within the jail walls. “Approximately 1,000 small panes of glass were broken out by inmates using long spear-like metal pieces from the florescent light fixtures. Similarly large windows throughout the second floor were also broken out.” Inmates smashed television sets, broke pipes, tore electrical fixtures off the walls, set mattresses, linens and clothing on fire, and plugged sinks, flooding large areas of the second floor. “The inmates tore a heavy 20-foot metal shelf, weighing about 300 pounds, from a washroom wall and used it as a battering ram to break out of their cells.” They worked their way outside into the recreation yard, apparently in hopes of escaping over the jail roof two stories above.

City law enforcement agencies volunteered to handle all calls for assistance within the county while the Sheriff’s units concentrated on the situation in the jail. Officers from the California Highway Patrol surrounded the building on the ground level while other officers were posted at strategic points on the roof. Members of the Sheriff’s Office and Santa Rosa Police Departments assembled on the second floor where they dispensed two pepper foggers, which disabled the rioters and forced them to retreat. The officers herded the inmates back down to the first floor where they were stripped of their clothing, searched and placed in mass in several large holding cells. Fortunately, no officers were hurt and three inmates received only minor injuries. The damage was so extensive that the Courts deemed the facility uninhabitable and ordered the transfer of 101 inmates to San Quentin Prison while repairs were made. The total loss was estimated around $75,000.

Once the jail was repaired, Sheriff Striepeke ordered deputies to back work in the jail to assist correctional officers in curtailing future violence. Correctional officers performed all the booking processes while the deputies acted as movement officers and were in charge of all the “hands-on” processes with the inmates. Sometime after, deputies were removed from the jail and full charge was once again given to correctional staff.

During the Ellis and Striepeke years, many ideas and tactics were tried to assist the individual deputy and the Sheriff’s office. These would entail the use of helicopters, dogs, underwater teams, four-wheel drive patrol vehicles and individual radio communication systems. Changes within the Sheriff’s Office were happening at a more rapid pace. With the continued crime fighting innovations in law enforcement and improved detention services, the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office continued to grow and advance.

As most of the more recent matters regarding the Sheriff’s Office will be more detailed in the following sections of this history book, a brief calendared overview of some significant events from the 1970’s through 2005 will follow:

In 1970, Joseph “The Baron” Barboza, a hitman for the New England Mafia, moved to Santa Rosa under the Witness Protection Program after he ratted off his bosses to Federal authorities. He shortly became a prime suspect in a murder case when one of his former mob associates, Clary Wilson was found in a shallow grave in Glen Ellen with two bullet wounds to the head. Law enforcement discovered Barboza had an argument with Wilson over a business deal and that Wilson’s wife and a girlfriend witnessed the shooting. Barboza was arrested and brought to trial under heavy security, as there was likely to be contracts out on his life. Barboza pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and served four years in prison before being released, once again, to the Witness Protection Program. Four months later, Barboza was gunned down in San Francisco.

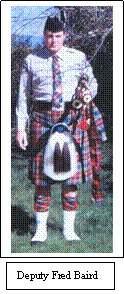

The Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office Bagpipe Band was created around 1970. The idea for the band started with a conversation between Sergeant John Young, Sergeant Fred Baird, and Dispatcher Bill Heath. After the initial conversation, they contacted members of the Bluebonnets (a local pipe band made up of private citizens) to discuss merging their band with a new Sheriff’s Office band. Forces were joined and the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office Bagpipe Band was born. Civilian band members were sworn in as special deputies. The band uniform consisted of a Sheriff’s Office uniform shirt and badge, a bonnet and kilt. The band played at ceremonial functions, Sheriff's Office funerals, and marched in many parades. The band was in existence for over 20 years.

In the early 1970’s, Ed Wilkinson, Mike Ross and Wayne Dunham (Coast Patrol) started the Sheriff's Office's first official K-9 units.

A mysterious killer who called himself “The Zodiac,” is suspected of murdering at least five people between 1966 and 1969. The Zodiac is known to have had victims in Napa and San Francisco and is suspected of many others in surrounding counties. In the early 1970’s, some of Sonoma County’s homicide cases were investigated for possible links to the Zodiac but turned up nothing conclusive. During the time of the murders and “…well into the 1970’s, (the Zodiac) sent dozens of letters, codes and diagrams to area newspapers detailing his crimes, taunting the police, threatening mayhem, and claiming to identify himself.” Nevertheless, the Zodiac has remained elusive to “…no less than four local police forces, the California State Department of Justice, the U.S. Postal Service, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Office of Naval Intelligence for over 30 years.” Even today, the identity of the Zodiac killer remains a mystery.

In 1971, Deputy John Swain became the first bomb technician for the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office Explosive Ordnance Disposal Unit. He was also the first to attend the original school for civilian bomb technicians, taught by the United States Army at the Presidio in San Francisco.

There were a series of homicides beginning in 1971 and ending in 1977, which involved eleven victims. The victims were females between the ages of twelve and twenty-three. Potential suspects included the Zodiac murderer and Ted Bundy. Although over the years, detectives have devoted countless hours to solving these crimes, the cases remain unsolved.

In 1972, salary for a deputy was $782 per month, paid once a month. What little overtime that was available was paid once a quarter.

In October of 1972, The Press Democrat headline read “Manson Link to River Slaying.” Aryan Brotherhood members Michael Monfort and James Craig, along with notorious Manson family members Pricilla Cooper, Stacy Pitman and Lynnette Fromme (a.k.a. “Squeaky,” and who incidentally, attempted to assassinate President Gerald Ford in 1975) were arrested in connection to the murder of United States Marine James T. Willett. Willett was shot through the head with a .38 caliber weapon and buried in a shallow grave on a mountain south of Guerneville. His wife, Lauren Willett, was also found murdered and buried in a similar grave in Stockton. Monfort was the first to be linked to the murders. He used James Willett’s identification after being arrested for robbing a liquor store. He later jumped bail. His recapture was shortly followed by the arrest of the other four suspects at a Stockton apartment, where officers located Willett’s discharge papers. The prosecution subpoenaed Cooper and Pittman to testify against Monfort and Craig. In an attempt to mock the law, Monfort and Craig managed to marry the women before the trial, making it illegal for the women to testify against their husbands. Nevertheless, Monfort and Craig were both convicted and served time for their crimes. After being paroled, Craig was shot numerous times, his body was stuffed in the trunk of a car and the car was set on fire on a Sacramento street.

In 1972, Dispatch operations began providing centralized, medical dispatch services to ambulance providers throughout the County via a dedicated phone line. This service was provided until July 1999, when “American Medical Response was awarded the EMS franchise contract and ambulance dispatching duties were transferred over to their system.”

In 1972, the Inspector’s Bureau was renamed to the Investigations Unit and inspectors were reclassified as detective sergeants.

During the summer of 1972, Sergeant Dale Moore with the approval of Sheriff Don Striepeke, formed a team consisting of nine deputies and one sergeant who rode in five, two-man cars labeled “Special Enforcement Detail.” The unit was designed to crack down on motorcycle outlaw gangs and other concentrated criminal problems. Sergeant Nick Speridon was the first (and only) sergeant of the SED Unit. “There was no member of SED that was more dedicated or harder working then Nick…Nick would never let you stand alone, regardless of the circumstances, should our acts or omissions be questioned.” Old enough to be the father of the nine deputies he was in charge of, Nick “felt personally responsible to the Administration and the public for ‘his mens’ actions.” Nick’s wife, Angie, would make “the boys” some food or coffee whenever they were in the neighborhood.

The SED Unit always worked together, never separating. Certain members of the team were even trained underwater divers and trained in cliff rescue. One member of each SED two-man unit was always subject to call-out. Members did not receive “specialty pay” for this position and overtime was only compensated in the form of time-off, at an hour-for-hour rate. Former SED member Deputy Mike Henry stated, “Over the years, much has been said about (SED) and the sergeant and deputies who were members of the unit. None of the members of SED were special in any way, nor was the unit comprised of deputies better than others…(but there) is an unspoken bond of brotherhood that exist between them as a result of having shared some experiences together.” SED disbanded in 1977.

In 1974, Douglas Edward Gretzler and Willie Luther Steelman were arrested and brought to our County under a change of venue for the robbery and murder. So notorious and feared were they, even the worst offenders incarcerated at our County jail threatened to riot if they were brought to the facility. Douglas Edward Gretzler (22) and Willie Luther Steelman (28) killed 17 people while on a rampage across Arizona and California. They killed Marine Captain Michael Sandberg and his wife Patricia on Nov. 3, 1973 by shooting them both several times in the head. On Nov. 6, 1973 they robbed grocery store owner Walter Parkin of $4,000 in cash and checks and killed all nine people who were inside his house just outside of Victor California. Among the victims were a nine-year old boy and an eleven-year old girl who were shot in the head as they hid beneath the sheets of a bed. The killers were arrested two days later in Sacramento. Among their possessions was a copy of the book, In Cold Blood written by Truman Capote about the murder of a Kansas family. Gretzler and Steelman later confessed to six additional murders. In 1987, Willie Steelman (who was an escaped mental patient before committing the murders) died of cirrhosis of the liver while on death row. Douglas Gretzler was executed by lethal injection at Arizona State Prison in Florence Arizona on June 3, 1998. He had been on death row since Nov. 15, 1976.

In the mid 1970’s, the Sheriff’s Office took over the responsibility of the Coroner.

Deputy Merrit Deeds was killed in the line of duty on August 23, 1975. After the murder of Deputy Merrit Deeds, in 1976 Sheriff Don Striepeke ordered that patrol units working outlying beat areas on swing and graveyard shift be two-man cars. This remained the norm until Sheriff Roger McDermott’s election in 1979. To increase exposure and curtail fiscal demands, patrol units returned to single-man cars on all shifts.

In 1976, Dale Moore was selected as the first Lieutenant of the newly formed Special Weapons and Tactics Team (SWAT), which was activated to perform negotiations and/or calculated force to control volatile situations. The current 38-member team consists of tactical, negotiation, dispatch, EMT and technician specialties. “The team trains twice a month, one day for tactics and one day for firearms,” with snipers receiving one additional day of training. Recently, the negotiations branch formed their own Unit, consisting of one sergeant, six negotiators, tactical dispatchers and a mobile command post. According to Deputy Jeff Dedischew, “Today’s SWAT owes the TAC Squad and SED gratitude for the sacrifices they made, the dedication they had for the Team and the Sheriff's Office and for the ‘take action’ reputation it gave to all of us.”

Detective Sergeant Ed Wilkinson was killed in the line of duty on April 17, 1977.

1979 saw the first Annual Challenge Bowl, starring our Sheriff's Office "Raiders". The annual football event donates proceeds to a different charity each year.

In 1980, Calvin Coleman shot and killed Patricia Niedig (34-years old) at her Chalkhill home near Healdsburg. He was convicted and sentenced to death row at San Quentin. His was the first death sentence handed down by a Sonoma County jury for crimes committed in this County since California voters reinstated capital punishment in 1978.

Deputies Bliss Magly and Brent Jameson were killed in the line of duty on October 23, 1980.

In 1981, Dispatch Operations moved to the Office of Emergency Services Building and was joined by Station 2 (Law 2). Today, Dispatch Operations “provides services to the Sheriff’s Office, Town of Windsor, City of Sonoma and the Santa Rosa Junior College…Approximately 150,000 law activities are processed annually.”

In the early 1980’s, Sergeant Prent Monson and Deputies Dennis Smiley and Chris Bertoli formed the first Street Crimes Unit.

In 1982, the first annual Sheriff’s Office Awards Banquet was held. Lieutenant Mike Brown, to honor the passing of fellow Deputies Brent Jameson and Bliss Magly proposed the event.

The County’s 9-1-1 phone system was activated in 1984. It displays the caller data on a screen, including the location of where the call originated from and the caller’s telephone number, along with the law, fire and medical agencies of jurisdiction.

In 1984, Support Services Manager Linda Klein was the first non-uniformed manager in the Detention Division.

In 1984, the County’s 9-1-1 emergency dispatch system was activated.

In 1985, the Sheriff’s Office Boating Unit was created.

In 1987, Sheriff Dick Michaelsen designed and implemented the current uniform shoulder patch showing the California Bear Flag (the official California State Flag) as its centerpiece.

In 1987, the Detention Division’s Specialized Emergency Response Team was formed and is responsible for crisis response during major facility emergencies at both the MADF and NCDF. The Team consists of 13 correctional officers, one correctional sergeant and one correctional lieutenant.

In 1988, Kirk Spaulding was the last “resident” deputy to be stationed in Geyserville, and Deputies Mario Jimenez and Steve Pederson were the first motorcycle units.

The Honor Guard unit was started in 1989 to represent the Sheriff's Office at ceremonies, parades and funerals. Commander Ihde approved official uniforms for the unit in September of 1989.

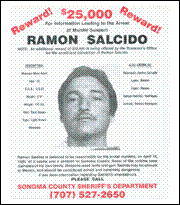

On April 14, 1989, a 28-year-old Sonoma Valley winery worker named Ramon Salcido killed seven people including his wife, his 2-year-old and 4-year-old daughters, his mother-in-law, his 8-year-old sister-in-law and 12-year-old sister-in-law, and his boss. He also cut the throat of his 3-year-old daughter but she miraculously survived. He shot another of his bosses but he also survived. Salcido was convicted and sent to San Quentin’s Death Row to await execution. This was the worst mass murder in Sonoma County history.

In the 1990’s, disguised as an ordinary jogger, a suspect hit houses near jogging trails and secluded areas that were a distance from any roadway. After breaking a window or a door with a large rock, the “Jogging Burglar” (a.k.a. “Open Space Burglar”) went directly to the master bedroom from which he stole only expensive jewelry items. The Jogging Burglar targeted homes in Petaluma, Cotati, Santa Rosa, and Sonoma as well as cities in Marin County. The Sheriff's Office teamed up with a detective in Marin in an attempt to solve the cases. Latent fingerprints were successfully lifted from seven houses and on two different occasions, the suspect was seen or chased from houses. Searches in DMV, military and criminal justice databases turned up negative and the identity of the burglar remained a mystery. The Jogging Burglar is credited with a total of 144 burglaries between Sonoma and Marin Counties, with a total loss estimated around $1,000,000. The burglaries suddenly ceased three years after they began and remain unsolved.

In 1990, Sergeant Mike Ferguson is credited with setting up the R-COP substation and Jim Piccinini was the first sergeant to run the program.

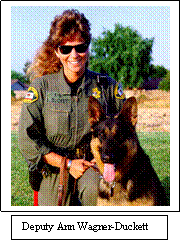

In 1990, Deputy Ann Wagner-Duckett became the first female K-9 handler for the Sheriff's Office.

In 1990, the first members of GRIT, the Gang Resources & Investigations Team (a precursor to today’s MAGNET) were detectives and Deputies Mike Ferguson, Bruce Rochester, Lorenzo Duenas, Dennis Smiley, Perry Sparkman, Joe Raya, Kevin Young, Jon Watson, Erick Gelhaus and Leslie Comrack.

In 1991, Alan Adams, a 19-year-old Santa Rosa Junior College student, told his friends that he wanted to steal some credit cards so he could buy some “nice things.” Adams drove towards the coast to find an isolated home. He stopped in Jenner, randomly choosing the home of Oscar (70-years-old) and Betty (60-years-old) Mann. “Carrying an assault-style rifle, he sneaked in through an unlocked door. Betty was washing dishes and Oscar was in his chair watching TV. Adams demanded their credit cards then fired more than 40 times.” Adams proceeded to use the stolen credit cards to purchase pornography and supplies for his gun. Despite the fact that Adams bragged about the crime to his friends, it would be a month before anyone would go to Sheriff’s detectives with information leading to Adams’ arrest. Adams was sentenced to life in prison.

In October 1991, the old County jail was closed and prisoners were transferred to the new Main Adult Detention Facility.

In 1992, the Sheriff’s Office Mounted Unit was reactivated. The Mounted Unit was first created during the 1960’s when Sheriff John Ellis rode his palomino in local parades. Sometime after that, it fell into inactive status until Lieutenant Mike Ferguson sought, and was granted, permission to reactivate it.

In 1993, Detective Barry Morris and his canine partner, Dillan, formed the Sheriff's Office's first narcotics K-9 team.

In October of 1993, Richard Allen Davis kidnapped Polly Klaas (12-years-old) from her home in Petaluma and murdered her. Davis was eventually arrested and sentenced to death. This case had a tremendous impact not only on Sonoma County but also on California as a whole. As a direct result of this case, the “majority of states now have legislation mandating prison for repeat offenders, including California where the law mandates a 25-year-to-life sentence for three-time felons. And many states have toughened laws involving criminals who prey on children…State lawmakers also overhauled the criminal information system making an ex-convict’s complete record more accessible to law (enforcement) agencies.” Locally, law enforcement agencies changed radio communication policies that previously restricted criminal broadcasts to individual jurisdictions. Additionally, the Polly Klaas Foundation was established to aid in the search for missing children.

In 1993, the Sheriff's Office's Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) system was put into operation.

In 1993, the Sheriff’s Office took on its first contract police agency by establishing the Windsor Police Department. Staff consisted of veteran deputy sheriffs and a Chief of Police. Future Sheriff Jim Piccinini was selected as the first Chief.

In 1994, the Larkfield substation was opened. Two owners of the Larkfield Center offered free space to the Sheriff's Office in hopes of increasing law enforcement presence in the area. From the time of our occupancy, it has served as a “storefront” more than a substation. Today, we lease the space and it co-serves as the headquarters for C.O.P.P.S.

In 1994, Dennis Brigham introduced the Sheriff's Office to the PIT (Pursuit Intervention Technique) maneuver.

In 1994, the sergeant of the first MAGNET Team (before it became a formal unit) was Bruce Rochester. In 1997, the unit became permanent and Lieutenant Jay Farmer was appointed as the first Manager and Sergeant Rob Douglas was appointed as the first Supervisor.

In the mid 1990’s, Lieutenant Erne Ballinger was instrumental in the Sheriff's Office procurement of the ALPS (Automated Latent Print System) or “Cal-ID” fingerprint database. Prior to us getting the system, we had to mail photographs of latent prints to DOJ. When the State introduced the system in the early 1980’s, they demonstrated that they could search a single latent print in 20 minutes, where if that same print were to be hand searched, it would take the entire staff of DOJ over 60 years. This system now enables us to not only search the criminal data base of approximately six million people but it also now allows us to search the applicant database, too, if we have all ten prints, that’s an additional eight million people. We can also link to other western states and we are connected to the FBI.

In 1995, the Community Oriented Policing and Problem Solving (COPPS) Unit was created. The purpose of the grant-funded program was to work directly with the community to solve local problems.

Deputy Frank Trejo was killed in the line of duty on March 29, 1995.

In 1996, Rich Sweeting was the first sergeant of the newly formed Domestic Violence/Sexual Assault Unit. Sweeting was instrumental in initiating the unit as well as getting it off the ground and running.

In 1997, Mario Robledo was appointed the first Gang Intelligence officer in the Detention Division.

In 1997, shortly after the permanent MAGNET started, there were a severe rash of gang involved violent crimes throughout the greater Santa Rosa area. Over the course of a few weeks, approximately 40 gang-involved shootings, stabbings, other felonious assaults and arsons took place. Nearly overnight, MAGNET and SRPD’s three gang investigators were augmented by 24 additional deputies and detectives, as well as officers from other county agencies. This reinforced MAGNET ran six days a week for six weeks. In the words of Judge Passalacqua, “…It’s a bad time to be a gang member with a gun in this county.”

In 1997, the average daily population of our Detention facilities was 960 inmates.

In 1998, Explorer Team members Zack Kelley, Dillon Moe, Amanda Lee, Eric Burgess, Sara Dickerson-Trimner and Rene Tanner went to their first competition. Out of 40 Explorer Posts, the team came in 2nd overall.

In 1998, Linda Suvoy became the first female to achieve the rank of Captain for the Sonoma County Sheriff's Office. Subsequently in 2007, Linda promoted as the first female Assistant Sheriff in the Sheriff's Office.

In 1999, the first official Environmental Crime Team was established under Sergeant Scott Dunn.

In 1999, Jan McKinley became the Sheriff's Office's first female sworn Lieutenant.

In 1999, Phil Gilbert became the first to successfully fill the Senior Department Information Specialist position.

In 2000, the MADF lobby underwent reconstruction so that the clerks could be completely enclosed behind a bullet-resistant glass wall.

In 2000, the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office (established in 1850) celebrated its 150-year anniversary.

In April 2002, the Sheriff’s Office occupied its new headquarters building on Ventura Avenue, Santa Rosa.

On July 1, 2004 the Sheriff’s Office began its second contract city law enforcement service with the Sonoma Police Department. Its first chief was John Gurney who was the former Sonoma Chief of Police. Chief Gurney stayed for one year as a contract employee, after which Sheriffs Lieutenant Paul Day assumed the role of Chief of Police.